Day 2 started early with breakfast in the hotel dining room at 7. We needed to have our luggage packed and ready to leave by 8. Today we would be making our way by bus across the island to Agrigento, stopping along the way to visit the ruins of Segesta and Selinus (also known as Selinunte). The exact timing and circumstances under which these cities were founded is not fully understood, but the first mention of them in a historical text occurs in 580 BC and at that time they were already engaged in hostilities with each other. These frequent border disputes would continue on throughout the centuries ahead, and would eventually draw in some of the region’s biggest power-players, with disastrous results for some of them. More on that later. First, we will go and explore the ruins of Segesta.

At the beginning of recorded history Sicily was divided between three indigenous tribes: the Elymians in the West, the Sikels in the East, and the Sicans in the middle: (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Segesta was one of the major settlements of the Elymians, and although the city was frequently allied with Carthage there is plenty of Greek influence here as well. Situated high on a hill in an area that was easily defended, the town included this magnificently preserved Greek theater where dramas and play would have been acted out:

As in the Greek theater in Pompeii, there are a few seats in the theater with names inscribed on them. This was done as a way of permanently reserving the seat for someone. On this one the letters “MA” stand out sharply from the ancient stone:

Something which I did not see in Pompeii last year was the presence of postholes in the area where the stage would have been. This is basically a change or disturbance in the soil which indicates that a wooden post was once inserted here. These posts would have served as the foundation of the theater’s stage. This close-up shot makes the neat square hole stand out:

There were several of these scattered around, but with a very obvious pattern to them that made it easy to see that this had once been a stage.

Standing just where the actors would have been many centuries ago, I got this view looking up at the semi-circular seats. As I was taking this picture an Italian tourist next to me threw his arms out and loudly exclaimed, “Senore, senori!” meaning, “Ladies and Gentlemen!” That is one of archaeology’s little joys: being able to find common experiences with people of other cultures across vast distances of space and time:

Also located here in Segesta is a Greek temple. This is a particularly important temple for scholars and historians because it was abandoned while still half-finished, leaving us a rare glimpse into the construction processes and techniques used to build these. Sitting very near the top of a hill and towering high above the rest of the town, the temple is quite a sight:

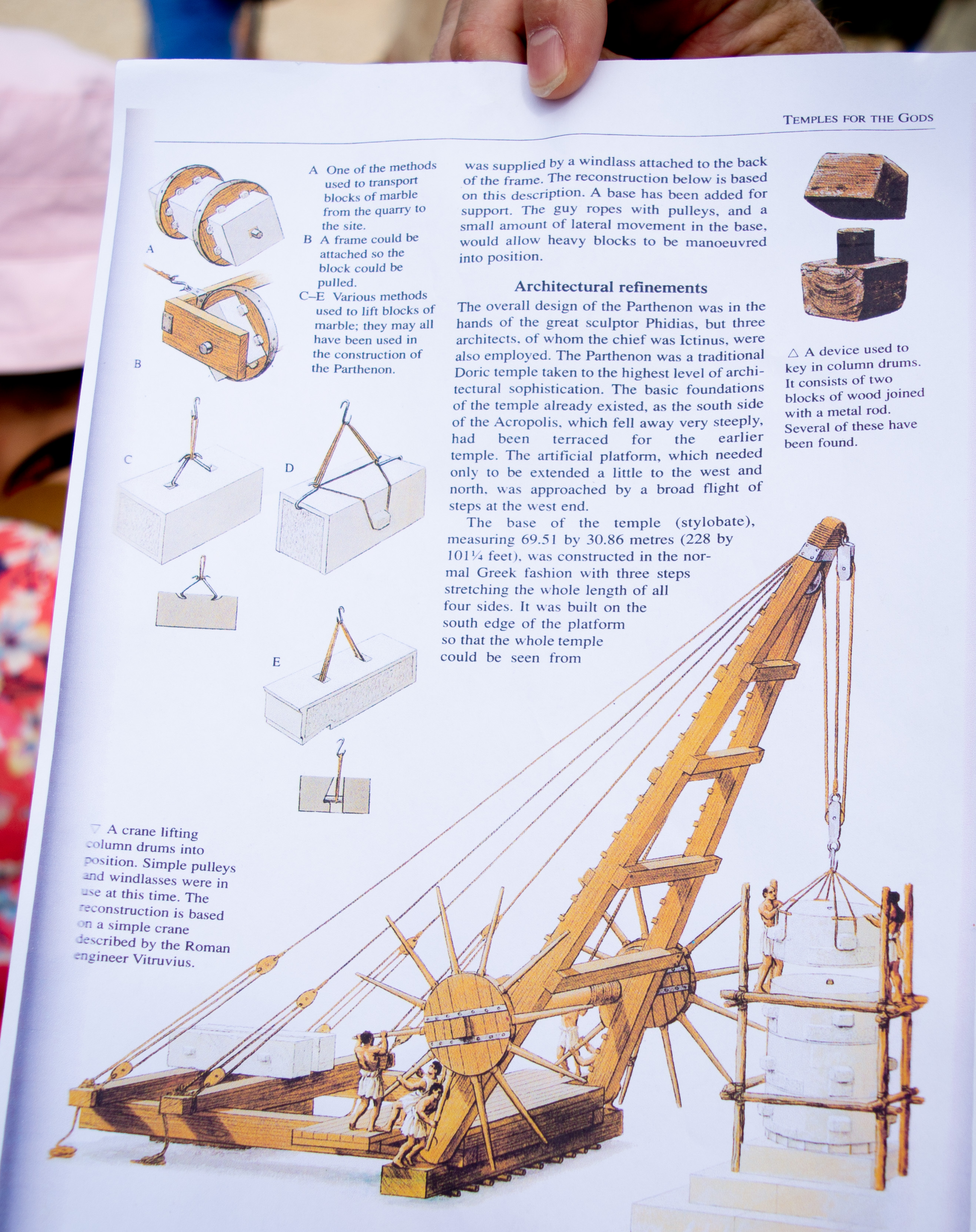

As we stood and marveled at this ancient temple, Denise passed around a series of pictures illustrating how these temples were probably built. One important thing to note is the presence of square protrusions around the outside of the blocks, which were used to attach ropes for lifting them into place:

These protrusions have been chipped off of the columns on this temple, but the columns have not been plastered or fluted yet, so we are left with a series of “donuts” for the columns. These columns also appear a bit too large for a typical Greek temple. This was done deliberately so that the columns could be trimmed to the exact size after they had been installed. It also allowed for little bumps, chips, and other mistakes during the construction process to be chiseled away later and leave the column appearing to be flawless.

Here are a few more shots of the temple as I walked around towards the rear:

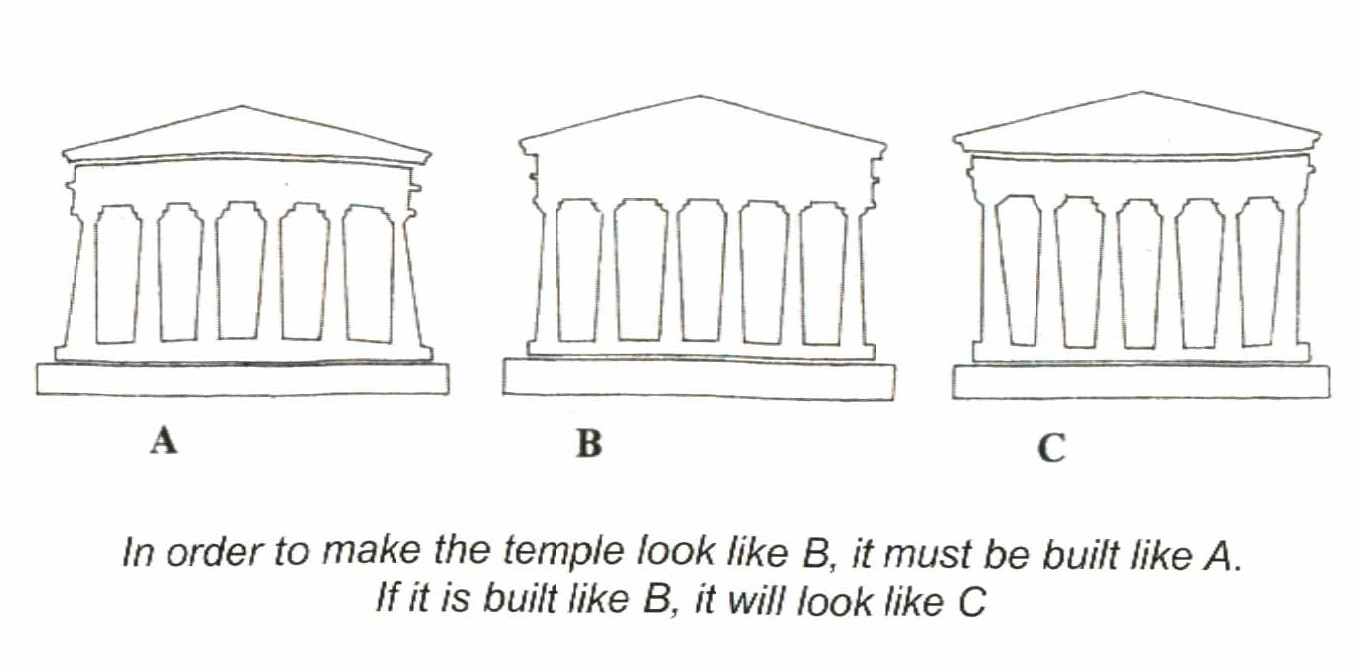

Standing at the corner of the temple and looking forward, I took this shot to show the little square protrusions which are still present on the stones that make up the platform of the temple. You can also see a slight upward curve in the platform. This was done because of an optical illusion that would cause the temple to appear to be bowed in the middle if it were built with perfectly straight lines. This picture below, taken from our Field Guide, demonstrates this principle:

At the tops of the columns are these square blocks, seen last year on the temples at Paestum (Day 2’s post):

On the completed temple these blocks have perfectly-formed corners, and I could remember seeing those last year and wondering how the Greeks managed to get those all the way up there without damaging any of the corners. Here at Segesta we can see just how they did it. The corners on this temple are not square, but spade-shaped. Once the blocks were safely positioned atop the columns these spades would be chipped off, revealing perfectly-squared corners just like at Paestum. The workers here never got around to chipping these spades off:

Unfortunately there is not much else to see here at Segesta because most of the site has not been excavated. So at this point we got back on the bus and made our way to the ruins of Segesta’s arch-rival, Selinus (known to the local Italians as Selinunte):

Located on the Southern coast of Sicily, Selinus is a city high on a hill surrounded by two rivers. It is a natural hot-spot for trading and commerce, and so it quickly became very wealthy and powerful. Thucydides wrote of this great wealth in his book “History of the Peloponnesian War,” as early as 416BC. That wealth enabled them to build a multitude of temples, of which at least 5 have survived. They are somewhat uncreatively named with letters (Temple A, Temple C, Temple E, etc.). Unfortunately the area is very seismically active, and earthquakes have taken their toll. Over the centuries these temples collapsed under earthquakes, and most of the pieces still lay scattered where they fell:

But fragments have remained standing, and in other places columns have been set back up. Here the remains of Temple C (built in 550 BC) tower over the broken fragments:

On the outskirts of the ancient settlement, the city walls and fortifications can still be seen:

Underground and just outside the wall, this network of tunnels would have allowed soldiers to rush out and launch an attack against any intruders:

Walking through the streets of Selinus was a somewhat similar experience to walking around the streets of Pompeii. Fragments of everyday life are to be found everywhere, including this grinder which might once have produced flour:

And this original mosaic floor, now over 2,200 years old:

Closer to the city center, this circular platform was once used as part of a wine or olive press:

With storm clouds closing in and the day near an end, we made a hurried visit over to Temple E, which sits on the East Hill nearby. Built around 470BC, this is a younger temple than Temple C. The four metopes from the outside of this temple were seen in the museum yesterday, and give us evidence of the progression of Greek art at this time. The exterior of the temple is quite impressive:

Seen here again is the slight curve in the platform which was necessary to make the temple look the way it does. But notice that on this temple the small square protrusions have been chipped off, providing a finished appearance:

The local yellow limestone, the same as that used elsewhere in Sicily, gives the temple a unique color:

We were free to walk up to the temple and to go inside it as well:

Being able to see all of the temple’s features, so well-preserved, was quite an experience!

With the rain now beginning to fall and the site preparing to close, we had to leave the temple to head back to the bus and finish our drive to the hotel near Agrigento.

At this point I should explain the historical significance of these two cities and the long-term consequences of their border disputes. I decided to save this part for the end of the post, since it is a bit lengthy and not everyone will be interested to know it. But for those who are interested, read on.

The episode in question takes place during a brief lull in the Peloponnesian War, a lengthy series of conflicts between Sparta and Athens that lasted from 434-401 BC and involved the Persians at times as well. The prelude to this war is a particularly fascinating stretch of history that encompasses some of the ancient world’s most famous battles. These include the Battle of Marathon (whose closing chapter involves a certain Greek messenger dropping dead after running a distance of 26.2 miles) and the Battle of Thermopylae (also known as the Last Stand of Leonidas, popularized by the film 300, the book Gates of Fire, and so very many others).

Both Athens and Sparta were being supported in this war by their respective allies, and the war was interrupted several times by short-lived peace treaties. During one of these brief lulls in the action, Segesta and Selinus got into another one of their border conflicts. After suffering a loss in the opening battle, Segesta decided to appeal to the area’s major power-players for help. Selinus had already enlisted the assistance of the nearby city of Syracuse, the most powerful city in Sicily, and so Segesta would need to find the most powerful ally it could. After failing to convince Agrigento and Carthage to come to their aid, the people of Segesta turned to Athens.

As Thucydides tells us in his book, the envoys from Segesta reminded Athens of an already-existing treaty between the two of them. They also warned that, if Selinus and Syracuse were successful, the defeat of Segesta would allow them to control all of Sicily, and possibly send a large military expedition to help the Spartans in an attack against Athens. Should this happen, the Athenian empire might well be destroyed. They promised Athens that they had a tremendous store of wealth which could be used to help fund the war, but first Athens had to join in on Segesta’s side.

The Athenian voters (Athens was a democracy by this time) were unsure. They decided to first send envoys to Sicily to see if Segesta really was as wealthy as the envoys claimed. This put Segesta in a very difficult position, because the statements they had made about the great stores of wealth in their city were all lies. So upon the arrival of the Athenian envoys, the Segestans gathered all of their gold and silver together and presented it to them. As the Athenians travelled from house to house the Segestans discreetly moved the precious metals and displayed them again, allowing the Athenians to believe that every house they visited had a vast store of riches. The Athenians apparently never caught on to the fact that they were seeing the exact same articles in every house they visited. It has even been suggested that the Temple at Segesta was started at this time as a way of showing the Athenian envoys how cultured and “Greek” their town was. The theory goes on to suggest that the construction of the temple was stopped once the Athenians decided to join the conflict.

The envoys returned to Athens with a report that Thucydides describes as being “as attractive as it were untrue.” Seduced by this report, the Athenians voted by the end of the day to send an army and a fleet of ships to Sicily.

This would turn out to be a disastrous military expedition for Athens. The full story is too lengthy to include here, but a long series of mistakes and blunders led to the complete destruction of the entire force. Out of the vast numbers sent to Sicily and the untold amount of public money that was spent (Thucydides does not even attempt to calculate the sum) very few would return to Athens. The Athenians heard of the defeat from foreign visitors and merchants, and at first could not believe it. One particular story survives of a customer in a barber shop talking of the defeat as if the Athenians would already have heard of it. The Athenians in the shop were as shocked to hear the story as the customer was to find that they did not already know about it.

With their army and navy now so greatly diminished and their treasury so drained, Athens could not hope to muster a sufficient defense against Spartan aggression. When the temporary peace collapsed, and hostilities between Athens and Sparta resumed, the Athenians predictably lost. They surrendered in 404 BC. Several of Sparta’s allies urged them to burn Athens to the ground and enslave all of the survivors. Sparta took a more merciful course and brought Athens into their sphere of influence, but not without changing the Athenian constitution to remove democracy from the city. Sparta did not approve of Athens’ experiment with democratic government. Democracy would make a brief comeback in Athens starting in 403 BC, but collapsed for good in 322 BC, which incidentally was the year after Alexander the Great died (the two events were not related). Humanity would have to wait many centuries for democratic systems to re-emerge as major players on the world stage.

Meanwhile, the defeat of the Athenian expedition meant that they were unable to influence the border dispute between Segesta and Selinus in a meaningful way. That conflict would have to be resolved by other means. Once Athens was permanently out of the picture it became clear that no one except Carthage had both the strength and the desire to control Sicily. Segesta was quick to sign an alliance with Carthage, and equally quick to urge them to attack and destroy Selinus. Carthage sent an army to do just that in 409BC. Agrigento and Syracuse promised Selinus that they would send reinforcements, but they did not arrive in time. Carthage surrounded and besieged Selinus, and after 9 or 10 days the walls were breached and the city was sacked. Although the area would continue to be inhabited after this time, the city never regained the wealth and power it had once known.

Segesta would meet her end too, in due time. The city was passed from Carthaginian hands to Roman ones during the First Punic War, and then experienced a period of wealth and peace. But eventually the city was sacked by barbarians, just like Rome itself, and was left destroyed. By 900 AD the area was completely abandoned. Even today most of it remains unexcavated.

That was the end of Day 2. Check back soon for Day 3, when we explored the ruins at Agrigento, also known as the “Valley of the Temples.” Stay tuned!