As we continued to make our way to the Forum the next building we entered was the Theater. Unlike the amphitheater shown earlier, which hosted sporting events, this venue would have hosted plays and dramas. The white marble seats are original, the others have been replaced after the theater was excavated.

Just outside the theater, we approached an old Greek temple which is thought to honor Athena. We were not able to enter the temple itself because excavation is still being done there. But we were able to see some pieces, including this one with ancient writing on it. We often think of Pompeii as being a 1st-century AD Roman city, but this temple reminds us that the Greeks were living here long before the Romans, and that parts of Pompeii were already 700 years old at the time of the eruption:

Next we went to the Stabiae baths, one of 4 public baths in Pompeii. This was a place where rich and poor alike would mingle while enjoying the rooms of various temperatures. Typically Roman baths would contain a cold room, a warm room, and a hot room. People would spend various amounts of time in each room to relax the body and open the pores. Sometimes there would be a large public pool as well. An exercise area might be located outside, with a changing area (like a locker room) located just inside. These baths include separate facilities for men and women. Walking up to the baths on our right, we first pass through the old exercise yard:

The first room we see inside is the changing room, with cubby holes in the wall to deposit your clothes and shoes as you enter the baths:

In this picture we see the ceiling of the Caldarium (hot room). Tony explained that the grooves in the ceiling allowed the condensation to collect and then run down the sides of the walls, instead of hitting the bathers:

Even though the room’s interior is damaged, a lot of the original plaster is still visible:

This shot provides a good view of the structure that exists beneath the caldarium floor. Stacks of tile were used to elevated the floor, leaving a void beneath. Hollow rectangular tiles run up the inside of the walls, allowing air to flow freely around the room. When the baths were in use, charcoal would be used to heat the air that was then circulated into the space under the hot room. The hot air would then rise through the tiles in the wall, artificially and evenly raising the temperature inside the room:

Since it was subjected to less extreme temperature swings, the tepidarium (warm room) is much better preserved. The artwork in here is beautiful:

As we approached the Forum I snapped this shot to show what a typical street looks like in Pompeii. With about 3 million visitors a year, it can get quite crowded:

Once inside the Forum, we can see Vesuvius towering over the city. This is one of the best shots of Vesuvius that I got on the trip, and I wanted to take the opportunity to explain exactly what we are seeing.

Most people look at the mountain and think that the current peak is the peak of AD 79, but as Tony explained, that is really the “pimple” that has risen as a result of the volcanic activity that has happened since then. The two lower peaks on either side of the “pimple” are the edges of the crater of AD 79. So if you draw lines extending up from those two points, you get an idea of how tall Vesuvius was prior to the eruption (and how much material was sent skyward by the explosion):

And here is the photo unedited:

Supporting this idea, here is a copy of the only known pre-eruption illustration of Vesuvius (interestingly, it is a fresco from a house in Pompeii). Notice how tall the mountain is, stretching up to a narrow point: (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The character wearing a suit of grapes while standing in a vineyard indicates that the slopes of Vesuvius were very good wine-growing territory. Even today it is possible to buy wine made exclusively from grapes grown on Vesuvius (I got to try some of that wine while I was there, more on that in Day 7’s post). The great Roman writer Pliny is known to have remarked that, in his opinion, the best wine in the entire world was that made in Campania in jars left in open fields.

If all of this seems strange, it is important to remember that in Roman times Vesuvius had been dormant for so long that no one could remember the last time it had erupted. As far as they could tell, it was perfectly safe to live there. Even Spartacus once camped his army on the mountain, having no fear of an imminent eruption.

Just North of the Forum is the only café in Pompeii, and upon reaching it we stopped to get some lunch. It was very crowded (it always is), but since leaving the site and coming back is not an option, it is really the only choice if you will be staying in Pompeii for the whole day. As you can imagine, the prices were expensive, but the portion sizes were generous so I didn’t mind. I had a panini, some chips, and a bottle of water. There are a lot of stray dogs in Pompeii, most of them perfectly tame, and they like to hang around the café to beg for scraps. This little guy tried to beg for a panini from a woman nearby:

While sitting here eating lunch we remarked that a time-travelling Roman would probably find the Forum to be a very familiar place: it is crowded and busy, with lots of folks sitting down to eat in the middle of the day, and a few friendly dogs hanging around, just as it would have been in Roman times. The clothing and the language have changed, and the ubiquitous use of selfie-sticks would look very odd to a time-traveling Roman, but otherwise the place looks very much the same as it did 2,000 years ago.

Moving North from the Forum we next entered the Forum Baths, and once again the artwork in here is quite impressive:

There is a washbowl here, with an inscription around the outside stating that it was donated by one Marcus Rufus. It further states that Rufus paid 5,250 sesterces for this bowl, which was an impressive amount of money considering that the average Roman soldier at this time only made about 900 sesterces per year:

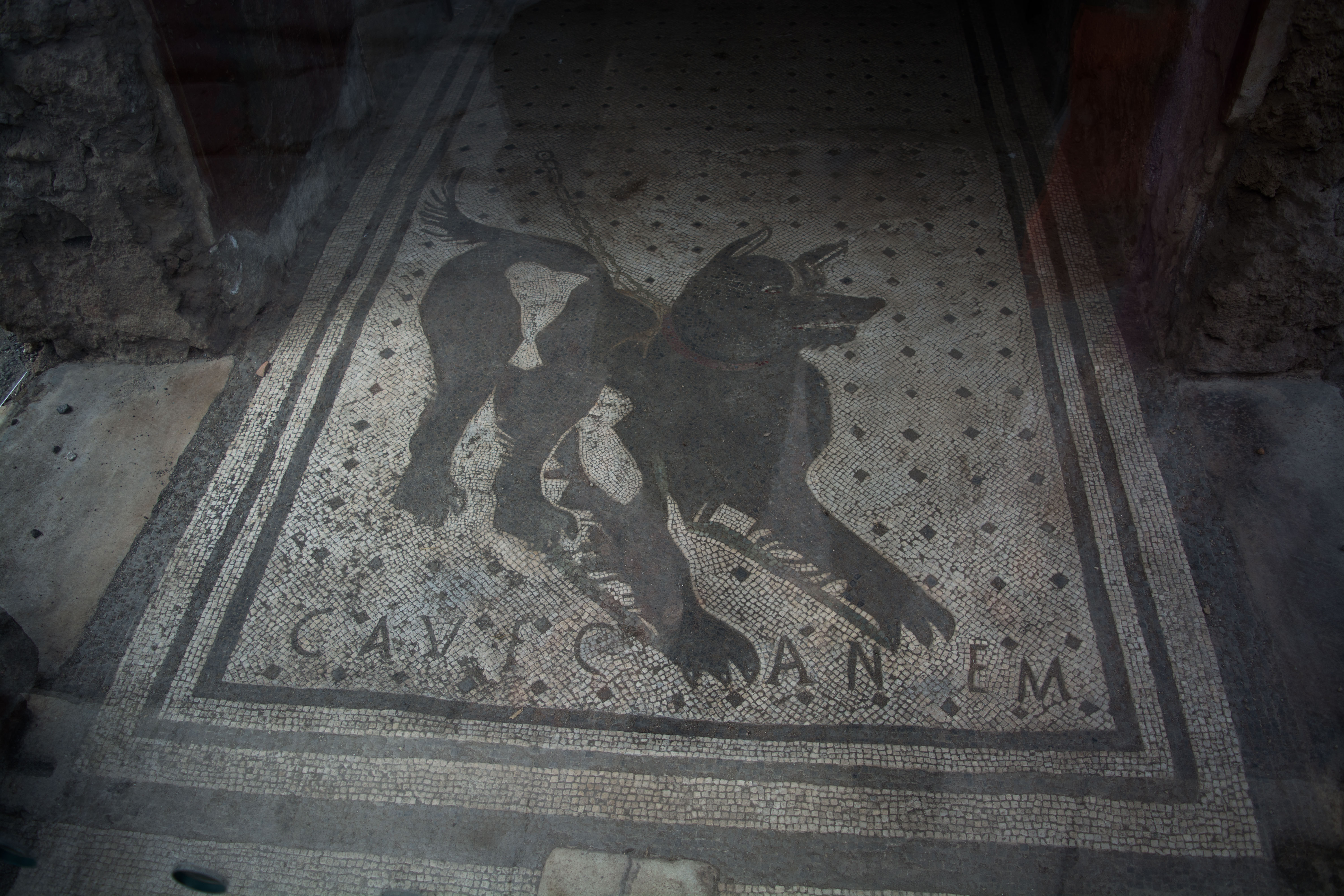

Moving further North towards the Herculaneum Gate, we pass the House of the Tragic Poet. This house was closed at the time, so we were not able to go inside, but we were able to see the famous mosaic of a dog at the entrance. Beneath the dog are the words “Cave Canem,” meaning, “Beware of the Dog”

Next we got to enter the House of Championnet. This was a rare opportunity, as Tony had never been inside this house before. Even our local guide had entered the house for the first time that same morning. At the rear of the house is a seaside terrace, and although the eruption buried the beaches and pushed the coast back (houses and trees now stand where the sea had been), you can still see what a beautiful view this once was:

Nearby we saw the Macellum (market), which had a beautiful shrine hidden behind a gate at the rear:

As we continue to move North, we pass an area where the ruts in the road are very clearly visible. Tony explained that he doesn’t think they would have been worn this deep by wheels alone, he thinks that they were cut in with tools early on. He also explained that by bringing a tape measure out here and measuring the space between the ruts, he was able to determine that the width of the axle on a standard Roman cart was 4 feet 8 ½ inches. This is a very interesting find, because in the early days of the railroad the width of the standard railway cart was also 4 feet 8 ½ inches. On the surface this makes it sound like the designers of the railroads used the streets of Pompeii to decide how wide to make their carts, but that is not the case. The railroad carts were designed to mimic the width of standard carts that were in existence before the railroad, and those carts were designed to mimic carts that existed before that. So it would appear that the width of the axle on a standard cart had not changed in over 2,000 years:

Tony also explained that the stepping stones in the middle of the street were placed there to allow people to cross the street without stepping in the street itself. This is because, while Pompeii did have running water, it did not have indoor sewers. So the people would use a bucket to go to the bathroom, and then throw the waste out into the street. Rain water would flush the waste downhill and out of the city. Having stepping stones allowed people to cross the street without stepping in the waste.

This next picture doesn’t have any remarkable monuments or frescoes in it, but it is one of my favorites and one that I really wanted to share, because it gives you a very good idea of what it feels like to stand on a typical street corner in Pompeii. It is not hard to imagine what the town would have looked and felt like before the eruption. Between the fountain, the street, the sidewalks, and the store fronts, it all seems so familiar:

Moving further North towards the Herculaneum Gate, we see a small restaurant with clay jars set into a marble-covered bar:

We also stopped to look at a bakery, which had a very familiar-looking brick oven for baking bread:

The stone hourglass shapes seen here were used for grinding grain to produce flour. Tony explained that the top part (shaped like an hourglass) slid over the lower part (shaped like a cone pointing up). The upper part would be rotated by a donkey, tied to a wooden beam that ran through the square hole in the middle. Grain would be poured in the top and fall through a narrow hole to the lower cone, then be ground between the two stone pieces as the donkey walked around in a circle. But since there isn’t enough room between each grinder for two donkeys to pass each other, they would have had to coordinate the movement of all the donkeys in the shop, which Tony referred to as the “Dance of the Donkeys”

We also found another water tower, this time with original lead water pipes still intact nearby. The pipes are protected by a fence, so I had to position the camera just right to get a good shot, but you can clearly see them here:

Some of the houses in this neighborhood had incredible frescoes on the walls:

We also found a spot where two lengths of lead water pipe have been joined together:

Moving further North we stopped to visit the House of the Faun. This is the largest, most luxurious, and most famous house in Pompeii. We are not sure who owned it, but clearly it belonged to a person of phenomenal wealth and power. The house included two large open-air gardens, joined in the middle by the famous Alexander Mosaic. This large and intricate mosaic is a copy of a Greek painting that no longer survives, depicting a battle between Alexander the Great and Darius III of the Persian Empire. I had seen it referenced in countless books and documentaries, but I did not realize how massive and impressive it really was. When I saw it in person, I was blown away. The original is in the Naples museum (pictures of it will be in Day 4’s post), but the replica shown here is nevertheless extremely impressive:

The small dancing faun figure that this house was named for has also been moved to the Naples museum, but a replica stands in the original spot:

At the front door of the House of the Faun there is a mosaic set in the sidewalk spelling out “Have,” (pronounced Hah-vay) a Roman greeting that was roughly equivalent to “Welcome”

As we near the Herculaneum Gate, we can see another stone grinder similar to the ones we saw in the bakery earlier. The stone has fallen apart in a way that makes it easy to see how the hourglass and the lower cone fit together:

Exiting Pompeii through the Herculaneum gate, we can see damage on the city wall from Sulla’s siege. As I mentioned in Day 2’s post, the Roman Republic had many allies in the Mediterranean area prior to the 1st century BC. But during the Crisis of the Roman Republic many of these allies turned against Rome, a period known to scholars as the Social War. One of the allies that turned against Rome was Pompeii. For such disobedience, the Roman general Sulla laid siege to Pompeii. Since damage is visible here and nowhere else on the wall, we know that once Sulla had the city surrounded he decided to concentrate his artillery fire here on the Herculaneum Gate. We can also tell from the small, shallow holes that the artillery he chose was a volley of lead-tipped arrows, designed to kill personnel but not to smash walls or buildings. Once the sentries were taken down, Sulla used a battering ram to smash through the gate, and then sent his soldiers rushing into the city:

This close-up shot shows a spot where an arrow struck a block on its corner, allowing us to see how the stone broke during the attack:

After the war, Sulla would go on to seize absolute power in Rome and give himself the title of “Dictator.” Even though Sulla eventually stepped down from power, his actions set a dangerous and destabilizing precedent for the Republic. Years later Julius Caesar would follow Sulla’s example to seize power for himself, and use the same title of Dictator. Julius Caesar, of course, was assassinated during the dying years of the Republic which would eventually give way to the Empire.

The last building we visited in Pompeii was the Villa of the Mysteries. Located on the outskirts of town, this building has magnificently preserved frescoes stretching all the way around several rooms. The frescoes in this room appear to show a rite of initiation for a young Roman girl, but the exact significance of the scenes remains uncertain:

The villa also had a wooden window shutter that had been cast with plaster, just like the bodies and the root systems seen earlier. The cast is so good that the original metal hinge (seen at the bottom) is retained in the exact location and position it was left in by the villa’s last occupant. It makes the place look so real, as if the eruption had occurred only yesterday:

Having now finished our day in Pompeii, we stopped by the gift shop on the way out and then went to Raphaelo’s Pub, where Tony has a happy tradition of drinking two large beers to mark the end of the tour. Having spent more than 8 hours talking all about Pompeii, the beers are well-earned. The rest of the group, myself included, joined Tony in drinking some authentic Italian beer called Peroni, which was quite good. I would be happy to drink it again.

That was the end of our day in Pompeii! For my next post I’ll cover Day 4, during which we saw the Naples Archaeological Museum, The Amphitheater at Pozzuoli, and the Piscina Mirabilis, a large cistern that was once connected to the Roman Aqueduct. Check back soon!